"He who is determined to write history in literary form should avoid the early history of Scotland."

A quote by the renowned historian A. O. Anderson from 1940

Still, it's

such a fascinating period, right?

Hill forts & other Early Historic fortifications

Click here for the Hill fort index

Once upon a time, virtually every hill in Scotland was donned with a fort, from the Bronze Age (2100-750 BC) and especially during the Iron Age (700 BC- AD 500). The Roman Occupation (mid-first century until early fifth century) changed a lot, even though the Romans never managed to occupy Scotland. They raided it a couple of times, but due to lack of resources, they never subdued the locals. The very southern part of Scotland was rather influenced by the Romans, the ones in the middle were bribed into some sort of "playing nice", but the northern part of Scotland - the Picts - were a troublesome nuisance to the Romans until the end of their time. Nice.

Of course, Scotland was not a unified territory under one over-lord, high-king, whatever. There were lots of territories ruled by their own kings, or lords, or leaders. And that required fortifications, loooooads of them. Some were abandoned after the Iron Age - like the Caterthuns - , but some continued to be used or even grew in importance.

Depending on the author, these types of fortifications are subdivided into different categories. Previously, they were subdivided like this:

1/ Fortified homesteads, such as brochs and ring forts

2/ Reoccupied hill forts

3/ Promontory forts (built on long, narrow pieces of land sticking out into the sea, think Dunnottar Castle-like)

4/ Citadel forts and nuclear forts

Now my first objection to this subdivision is that a reoccupied hill fort could easily be a promontory fort

or develop into a citadel or nuclear fort. Dundurn is a prime example of that.

Other historians/archaeologists break them down by structure/set-up:

* forts defended by a simple wooden palisade

* univallate forts (one raised edge or wall)

* multivallate forts (more than one rampart or defensive structure)

* ring forts with outworks

* large forts (the nuclear ones) with hierarchically arranged enclosures

Fun, right.

Why not simply list them alphabetically and see for yourself.

For those with an appetite to explore all the hill forts on the British Isles, there is an online atlas.

Index

Burghead // Caisteal Dubh // Caisteal Mac Tuathal // Caterthuns // Craig Mony // Craig Phadrig // Dun da Lamh // Dun Deardail // Dundurn // Dunnicaer // Knock Farril

Burghead

Now until the early nineteenth century, this Pictish fort was a truly impressive fort with its remains visible for even those without the slightest sense of imagination. A multivallate fort containing three ramparts filling the entire promontory sticking out into the Moray Firth. Really, take a map, or go on the online atlas and look how deep the promontory extends.

Now until the early nineteenth century, this Pictish fort was a truly impressive fort with its remains visible for even those without the slightest sense of imagination. A multivallate fort containing three ramparts filling the entire promontory sticking out into the Moray Firth. Really, take a map, or go on the online atlas and look how deep the promontory extends.

And then realise how civilisation ruined this gigantic Pictish fort.

In the early nineteenth century the defensive ramparts were used to build the harbour, while a new town was constructed over most of its remains. Really, only the very tip of the fort remains.

This tiny bit is what is left. The white building in the middle is a small museum which houses some fragments of the Burghead bull.  Apparently some thirty of these Pictish stones were spread around Burghead. Unfortunately, all of the fragments in the museum are kept behind glass, with poor lights, so the example to the right is one from Elgin Museum.

Apparently some thirty of these Pictish stones were spread around Burghead. Unfortunately, all of the fragments in the museum are kept behind glass, with poor lights, so the example to the right is one from Elgin Museum.

In Burghead town you can also visit the well, which was part of the fort. Various theories exist concerning its purposes.

Archaeological excavations on the beach are revealing further details of how extensive this structure must have been.

It is really tragic how negligent society can be.

Caisteal Dubh - Castle Dow

How dull can one be? The black fort/castle. So this one doesn't score points for originality.  So I'm assuming the individual(s) responsible for erecting the cairns some time during the Victorian Age, must have thought the same and handed it some imaginative features.

So I'm assuming the individual(s) responsible for erecting the cairns some time during the Victorian Age, must have thought the same and handed it some imaginative features.  They look odd and no one has any idea what they are meant to be. Fact is they're numerous and they distract you from what you really should be seeing: an Iron Age hill fort.

They look odd and no one has any idea what they are meant to be. Fact is they're numerous and they distract you from what you really should be seeing: an Iron Age hill fort.

If that's not bad enough, the hill fort's many ramparts are damaged by the construction of a sheepfold. I kid you not. The sheep would have been high (not dry), as the fort is - as are all of them - quite a steep climb up. But nicking stones from a Pictish construction to build a sheepfold. Sigh.

If that's not bad enough, the hill fort's many ramparts are damaged by the construction of a sheepfold. I kid you not. The sheep would have been high (not dry), as the fort is - as are all of them - quite a steep climb up. But nicking stones from a Pictish construction to build a sheepfold. Sigh.

But as you can see from this picture, some remnants are there for the naked eye to behold.

But as you can see from this picture, some remnants are there for the naked eye to behold.  You can still make out several walls measuring a few metres thick and to create a better view of the fort from below, they felled some trees (and left the wood).

You can still make out several walls measuring a few metres thick and to create a better view of the fort from below, they felled some trees (and left the wood).

If you want to visit hill forts, don't do it alphabetically, because this is not one to start with. I liked it very much, but it's not the most "imaginative" one. Caisteal Dubh is in Grandtully Forest, not too far from Aberfeldy. A walking trail from the Forestry Commission will guide you.

Caisteal Mac Tuathal

Most hill forts are anonymous. You can date them, and if you are lucky - like with Dundurn below - you can link them to an event. But this hill fort has a name, a proper name to it.  This was the private hill fort of the son of the abbot of Dunkeld (849-865 AD), the ecclesiastical capital of the Scottish kingdom for some two centuries. Caisteal Mac Tuathal - fort of the son of Tuathal. How brilliant is this?

This was the private hill fort of the son of the abbot of Dunkeld (849-865 AD), the ecclesiastical capital of the Scottish kingdom for some two centuries. Caisteal Mac Tuathal - fort of the son of Tuathal. How brilliant is this?

Unfortunately, not a lot is left. And what is left of it, is very hard to take pictures of. Trust me, I took plenty, but apart from single rock slabs and fragments of outer walls sticking out of the grass, the best pictures are the ones of the entire complex.  Still, I loved discovering the rather impressive contours and the insides of the caisteal, and in many ways, it reminded me of Dundurn which I visited earlier: the rock slabs at the summit, the rocks where you can just picture more (I have a vivid imagination). When standing on top of the structure, you realise you are quite elevated as well.

Still, I loved discovering the rather impressive contours and the insides of the caisteal, and in many ways, it reminded me of Dundurn which I visited earlier: the rock slabs at the summit, the rocks where you can just picture more (I have a vivid imagination). When standing on top of the structure, you realise you are quite elevated as well.

Caisteal Mac Tuathal is situated on Drummond Hill, Kenmore, and you can find it when you follow these neat signs posted by the Forestry Commission. A proper Pictish boar.

Caisteal Mac Tuathal is situated on Drummond Hill, Kenmore, and you can find it when you follow these neat signs posted by the Forestry Commission. A proper Pictish boar.

Caterthuns

The White and Brown Caterthuns are two spectacular hill forts on each side of a little road between Brechin and Edzell. (SatNav is useful - we drove around it for ages before finally finding it.) One side leads to the White Caterthun - that's the one above. The other side is the path to the Brown Caterthun (see below). We didn't explore that one because a thundercloud was too close for comfort. But as the White Caterthun is - with its 298 metres - slightly higher than its peer (287m), you can takes great pictures.

Both hill forts date from at least the first millennium BC and it is guessed they had different functions: military and ceremonial. The Brown Caterthun however, had nine entrances, so the chances it was constructed purely as a defensive structure are rather slim. Still, both caterthuns have various earthworks as defences: stone and turf ramparts, ditches, palisades... The whole lot. Over time they were expanded, rebuilt and remodelled. Grand make-overs in ancient times.

Both hill forts date from at least the first millennium BC and it is guessed they had different functions: military and ceremonial. The Brown Caterthun however, had nine entrances, so the chances it was constructed purely as a defensive structure are rather slim. Still, both caterthuns have various earthworks as defences: stone and turf ramparts, ditches, palisades... The whole lot. Over time they were expanded, rebuilt and remodelled. Grand make-overs in ancient times.

The White Caterthun has the most visible - stone - remains. It has an inner and outer wall, with a stone with cup and ring marking in-between the two.

The White Caterthun has the most visible - stone - remains. It has an inner and outer wall, with a stone with cup and ring marking in-between the two.

The great stone fort would have been metres high and apparently there are traces of vitrification (I can't begin to imagine the effort to do that to a construction this size).

Inside the huge oval, there were roundhouses and other "buildings", as well as a stone-filled pit.

Inside the huge oval, there were roundhouses and other "buildings", as well as a stone-filled pit.

You can go "deep" into the fort on a wee path, or you can explore the structure by walking on the stone ditches and marvel at the sheer size of it.

If it doesn't pour buckets as soon as you finish exploring one Caterthun, and you feel like relaxing a bit, there's a picnic table at the bottom of the path leading to the White Caterthun.

What are you waiting for? SatNav?

Craig Mony

Nothing much is left of this hill fort and as a small promontory fort, it is fair to admit that is considered less of a fort than a local viewpoint towards Lewiston and especially Urquhart Bay.

Nothing much is left of this hill fort and as a small promontory fort, it is fair to admit that is considered less of a fort than a local viewpoint towards Lewiston and especially Urquhart Bay.

But still, some can sense the atmosphere (some absolutely do not). There are rocks, there is a feeling of natural defensive structures... I liked it.

But still, some can sense the atmosphere (some absolutely do not). There are rocks, there is a feeling of natural defensive structures... I liked it.

Craig Phadrig

There are a few Pictish forts whose names ring more of a bell than most. Craig Phadrig is certainly one of those. Now the name doesn't give away a great deal: Craig Phadrig, Patrick's rock.

There are a few Pictish forts whose names ring more of a bell than most. Craig Phadrig is certainly one of those. Now the name doesn't give away a great deal: Craig Phadrig, Patrick's rock.

The Picts themselves left precious little evidence in written documents, so it is religion which may give tantalising clues about this hill fort. It just happens that the most famous saint in Scotland - St Columba - visited the Pictish king, Bridei, in the sixth century.  And this visit occurred in the vicinity of Inverness.

And this visit occurred in the vicinity of Inverness.

Craig Phadrig is the most important contender for that saintly visit. Which means that this fine hill fort is no less than a royal residence.

You can explore this royal fort yourself at a car park designated for this very purpose. It is an easy walk on a good path, though naturally, the hill necessitates a wee bit of a climb. Surely that is the very nature of a hill fort. But nothing too strenuous.

At the bottom of the hill there's a board with some information, including a picture of what the fort may once have looked like: some huts/buildings inside a double rampart. Then do take the advice reading: "Head up to the summit to see the grass-covered remains of the fort."

At the bottom of the hill there's a board with some information, including a picture of what the fort may once have looked like: some huts/buildings inside a double rampart. Then do take the advice reading: "Head up to the summit to see the grass-covered remains of the fort."

I admit, it takes some imagination... which my other half does not have. While I was near-extatic to explore every inch of this - what the hill forts database calls - "spectacular fort" with its massive vitrified structure of two defensive walls... my other half looked bemused. So much enthusiasm for grass. And bluebells.

Another board offers views "well worth the effort". Unfortunately, when we were there, banks of "haar" promenaded over the hill, obscuring any sort of view.

Another board offers views "well worth the effort". Unfortunately, when we were there, banks of "haar" promenaded over the hill, obscuring any sort of view.

But the fort was no less impressive.

So when you are in the vicinity of Inverness and you feel like visiting a royal fort, climb up to Craig Phadrig. It's definitely more than grass and bluebells, even if some will roll their eyes.

Dun da Lamh

You should pronounce this dun as "dun da Larve" and it has nothing to do with lambs, but everything with "fort of the two hands". Three sides of this fort are impregnable and the only accessible side had defences with walls of over 6m and up to 7.5m thick.

You should pronounce this dun as "dun da Larve" and it has nothing to do with lambs, but everything with "fort of the two hands". Three sides of this fort are impregnable and the only accessible side had defences with walls of over 6m and up to 7.5m thick.  The rocks used to construct these walls are not from this strath and weigh at least 5,000 tons. How's that for labouring to build a fort?

The rocks used to construct these walls are not from this strath and weigh at least 5,000 tons. How's that for labouring to build a fort?

It is guessed that this fort is from the early Pictish period.

Governmentally condoned vandals are of all periods. As you reach the top of Dun da Lam, you will find a neatly constructed shelter, built during the 1935-1945 period, when - unless I'm seriously mistaken - no more enemies were intent on capturing Black Craig, the hill on which Dun da Lamh is situated.

Dun da Lamh can be visited as part of the "Black Wood and Dun da Lamh fort" walk on Walkhighlands - Cairngorms - Kingussie and Newtonmore. The closest car park is the one at Laggan (Wolftrax). This walk is signposted and well worth it. The views are stunning. Before you reach the fort, this is the panoramic vista you can gaze at.

Pretty stunning, right?

Dun Deardail

Dun Deardail is an iron-age fort in Glen Nevis and up until 2015 very little was known about it, apart from the fact that it was vitrified and that it was built around 2,000 years ago. According to a board not far from the site, the people living there had "colourful flags and banners proclaiming the power of the tribe to which they belonged". It was/is described as a "natural stronghold with amazing views". Given the mighty Ben Nevis is situated in full view, that last bit is undeniably true.

Dun Deardail is an iron-age fort in Glen Nevis and up until 2015 very little was known about it, apart from the fact that it was vitrified and that it was built around 2,000 years ago. According to a board not far from the site, the people living there had "colourful flags and banners proclaiming the power of the tribe to which they belonged". It was/is described as a "natural stronghold with amazing views". Given the mighty Ben Nevis is situated in full view, that last bit is undeniably true.

In 2015 this dun was finally excavated for the first time. A massive thick dry stone wall of at least 5m thick and presently still 2.8m high was uncovered (the 2015 dig did not reveal the outer wall face of that wall, which says something about its size). There was clear evidence of vitrification, but this did not mean the end of Dun Deardail's occupation. On the contrary, after the ramparts collapsed, they were rebuilt and the hillfort was reoccupied. The archeologists also found evidence of people living on the terraces below the hillfort.

More archeological digs coming up.

More archeological digs coming up.

Dun Deardail is associated with the story of Deirdre of the Sorrows, an Irish legend about the beautiful Deirdre, who fled to Scotland with her lover. As often is the case, tragedy is the backbone of the story. Her lover is killed by a rival and when taken by that rival, Deirde ultimately commits suicide. Deep sigh.

Visiting Dun Deardail is very easy, as it is signposted from Glen Nevis and the track to it follows quite a bit of the West Highland Way. You can also find the walk via Walkhighlands - Fort William.

Visiting Dun Deardail is very easy, as it is signposted from Glen Nevis and the track to it follows quite a bit of the West Highland Way. You can also find the walk via Walkhighlands - Fort William.

I had a particular interest in this dun, as I used one of the pictures above for the cover of The Rampart Inside. Always useful exploring the terrain before writing about it.

Dundurn

Dundurn is one of the finest examples of a hill fort.  Aye, and you noticed that correctly, it is the same picture I used as the banner for the history section. Says something, right?

Aye, and you noticed that correctly, it is the same picture I used as the banner for the history section. Says something, right?

I'll tell you more. Mind possible golf bals flying around your head and even visit it yourself. Dundurn is situated in Strathearn, at the eastern end of Loch Earn, at St Fillans.  The ruined chapel of St Fillan's is nearby, which is why Dundurn is sometimes also called St Fillans Hill. But it's not St Fillans. It's Dundurn. It's really a dun, a fort, a Pictish fort at that.

The ruined chapel of St Fillan's is nearby, which is why Dundurn is sometimes also called St Fillans Hill. But it's not St Fillans. It's Dundurn. It's really a dun, a fort, a Pictish fort at that.

Under the influence of William Forbes Skene it was believed for a long time that Dundurn was the capital of Fortrenn, but as Fortrenn is now thought to be in Moray - so northern Pictavia - it cannot have been the "main" fortress. But it must have been important none the same, as that great Pictish king Bridei son of Beli considered it necessary to besiege it in 683. Another king, King Girg, son of Dungal, died at Dundurn in 889, so until the end of the ninth century, this fortress certainly had royal interests.

Dundurn is a multi-phase fort, the defences of which were strenghtened several times between the sixth and ninth centuries.

In its first phase, the pyramid-shaped hill had a crag defended by a wooden palisade.

Then it was improved by a simple ring fort, the so-called "citadel", which was protected by outworks.

In its final stages - probably after its destruction in 683 - Dundurn was rebuilt and turned into a proper nuclear fort.

Hardly anything remains today and to the uninterested eye, this dun represents nothing more than a lump in the landscape, a

tiny dot of a hill with a lot of scree covering its sides.

Hardly anything remains today and to the uninterested eye, this dun represents nothing more than a lump in the landscape, a

tiny dot of a hill with a lot of scree covering its sides.

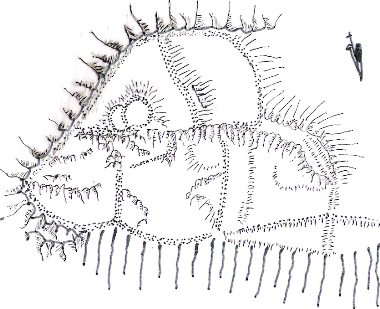

But it's not scree. Every single bit of loose rock on that hill was part of the defences of that formidable fortress. All the dots on the sketch to the right (apologies, aye, this is my handiwork) are man-made defences. So that's a lot of them.

As you can see from the sketch (at least, I hope you can), the south and east were protected by steep sides, so the builders of this fort focussed on the north and west.  Even today, you can only climb to the top via the west and the final bit is reached from the north (that's the picture to the left).

Even today, you can only climb to the top via the west and the final bit is reached from the north (that's the picture to the left).  The steep precipice is what you can see on the right. Nope, no assailant is going to send an army via the southern side of Dundurn.

The steep precipice is what you can see on the right. Nope, no assailant is going to send an army via the southern side of Dundurn.

From a bit lower, the steep crags look even more impressive. When you walk around the hill, you really wonder how you are going to get to the top at all.

The upper terrace was ringed by a massive rampart. Three lower enclosures had similar ramparts constructed around them. Dundurn was not some lowly fort.

The picture below was taken at the top. It was extremely windy up there and I thought the view was extraordinary. Nothing remains but rocks and stones. Aye, it takes a wee bit of imagination to picture a formidable fortress on top of this conical hill. (I manage quite easily, but my other half finds these places less impressive.)

When an attempt was made to excavate the site in the late seventies, the team underestimated the depth of the productive archaeological layers that tell something about how people lived there, so most of this enclosure remains a mystery, much like the Picts themselves.

Go check it out for yourself.

But mind the golf balls.

Dunnicaer

A very special one, this one. The Dunnicaer Sea Stack - close to Dunnottar Castle in Stonehaven - may well be one of the oldest Pictish forts, as carbon dating confirms this site had a Pictish presence as far back as the third century. Up till now, no older site has been discovered. As you can see from the picture, it would have been a very defensive structure as it has sheer drops on all sides.

Archeologists have known for quite some time Dunnicaer had to be something special, as five Pictish Class I symbol stones were discovered in the nineteenth century. Well, "discovered" is a fancy definition for some youthful adventurers who - on not finding the promised pot of gold there - found decorated stones instead and subsequently threw them into the sea. When other Pictish stones made the news a few years later, the youths must have remembered them and at east five stones were recovered.

Archeologists have known for quite some time Dunnicaer had to be something special, as five Pictish Class I symbol stones were discovered in the nineteenth century. Well, "discovered" is a fancy definition for some youthful adventurers who - on not finding the promised pot of gold there - found decorated stones instead and subsequently threw them into the sea. When other Pictish stones made the news a few years later, the youths must have remembered them and at east five stones were recovered.

In Pictish times the sea stack may have been a promontory, but nowadays it is most certainly a very individual sea stack, so the archeologists excavating the site in 2015 needed mountaineers to get there. What they found was evidence of a significant fort with ramparts made of stone and timber. The sea stack/promontory appears to have been larger back then as well. Archeologists assume that the site was relatively short-lived and that the Picts may have moved their "lodgings" to the nearby site of

In Pictish times the sea stack may have been a promontory, but nowadays it is most certainly a very individual sea stack, so the archeologists excavating the site in 2015 needed mountaineers to get there. What they found was evidence of a significant fort with ramparts made of stone and timber. The sea stack/promontory appears to have been larger back then as well. Archeologists assume that the site was relatively short-lived and that the Picts may have moved their "lodgings" to the nearby site of  Dunnottar Castle. Still a promontory, it has equally impressive drops on three sides and may just have been slightly more comfortable in size.

Dunnottar Castle. Still a promontory, it has equally impressive drops on three sides and may just have been slightly more comfortable in size.

The castle you can visit and is definitely worth doing so, even though you will find no trace of a Pictish presence. The Dunnicaer Sea Stack can be admired from a distance when you walk along the coastal path from Stonehaven to the Castle. Needless to say, I was very impressed by it.

Knock Farril

Knock Farril or Knockfarrel is an Iron Age hill fort which was the seat of a Pictish king. It may have been used and reused at various periods in its history.

It is located in Strathpeffer, and can be seen from the Eagle Stone, a fine Pictish stone picturing a horseshoe and an eagle.

It is located in Strathpeffer, and can be seen from the Eagle Stone, a fine Pictish stone picturing a horseshoe and an eagle.

To walk towards this magnificent hill fort, start at the Blackmuir Wood car park. A signpost is provided.

To walk towards this magnificent hill fort, start at the Blackmuir Wood car park. A signpost is provided.

There are two ways up the hill fort. You can stay on more "level" ground, or you can go uphill and walk on a fine ridge.

There are two ways up the hill fort. You can stay on more "level" ground, or you can go uphill and walk on a fine ridge.

Do take the ridge. It's not that great an effort and the views can be spectacular... though "haary" ("haar" is the fog typical for the large area around the Moray Firth, persistent enough to spoil views and intense enough to swallow bens, glens and firths). But still, do take the ridge. As you can see, it's wide and easy to walk. According to locals, it offers the best views in Scotland, although that is debatable.

Whatever route you take (unless you walk from Dingwall), you will arrive at this point. Not much hesitating how to tackle this beauty, right?

Whatever route you take (unless you walk from Dingwall), you will arrive at this point. Not much hesitating how to tackle this beauty, right?

At the bottom of the hill, there's a board with some information, including a picture of what the fort must have looked like: a substantial residence with massive ramparts. You can spend quite some time exploring the entire site. Traces of two wells and of a rectangular building are visible. When I enthusiastically stand on a Pictish hill fort, my other half usually laughs and says it is just a hill with grass. For those without much imagination, Knock Farril is where history is tangible.

At the bottom of the hill, there's a board with some information, including a picture of what the fort must have looked like: a substantial residence with massive ramparts. You can spend quite some time exploring the entire site. Traces of two wells and of a rectangular building are visible. When I enthusiastically stand on a Pictish hill fort, my other half usually laughs and says it is just a hill with grass. For those without much imagination, Knock Farril is where history is tangible.

The board tells you something else as well. It reads that this hill fort is "one of the finest examples of a vitrified fort anywhere in the world".

Now thàt is not debatable. For real. You can see it with your own eyes. Take a look at this picture to the right. You can clearly spot the blackened bits where the rocks were heated so much they vitrified.

Now thàt is not debatable. For real. You can see it with your own eyes. Take a look at this picture to the right. You can clearly spot the blackened bits where the rocks were heated so much they vitrified.

Knock Farril is a magnificent hill fort and a great walk. Combine it with a visit to the stone maze, which is constructed from rocks from all over Scotland. But most of all, do take your time marvelling at this fantastic hill fort... no matter if some will still call it a hill with grass.

Home

Home